07 November 2021: Clinical Research

Challenges for Polish Community Pharmacists in Provision of Services to Immigrants and Non-Polish-Speakers in 2018

Marcin Plombon1ABCD, Urszula Religioni2CDEF*, Agnieszka Neumann-Podczaska3F, Piotr Merks14ABCDGDOI: 10.12659/MSM.933678

Med Sci Monit 2021; 27:e933678

Abstract

BACKGROUND: International patient services in community pharmacies are becoming increasingly common. The growing number of immigrants, as well as the developing trend of medical tourism, make it necessary to provide these people with access to healthcare services, including pharmaceutical services in generally accessible pharmacies. Serving non-Polish-speaking patients, however, requires both fluent specialist knowledge of a foreign language and interpersonal skills. These skills can greatly influence the proper use of medications by patients. This study aimed to investigate the reported challenges for Polish community pharmacists in the provision of services to immigrants and non-Polish-speakers in 2018.

MATERIAL AND METHODS: The study included 98 pharmacists and pharmaceutical technicians from community pharmacies in Poland. The research tool was a questionnaire sent to pharmacy staff in cooperation with pharmacy councils in 2018.

RESULTS: Analysis of the data gathered using a 5-point Likert scale showed that the participants rated the preparedness for international patient services in pharmacies as medium (mean 2.76±1.33). The mean foreign language knowledge score was 2.99±1.29. The participants indicated a low possibility of acquiring these language skills (mean 2.53±0.91), and emphasized that patients from abroad rarely asked about the use of the medications (mean=2.20±1.06).

CONCLUSIONS: This study showed that in 2018, pharmacy staff in Poland did not feel adequately prepared to provide comprehensive pharmacy services for immigrants and non-Polish-speakers, with concerns of non-compliance with medications due to poor communication.

Keywords: Adolescent Health, Attitude of Health Personnel, Community Health Services, Communication Barriers, Community Pharmacy Services, Emigrants and Immigrants, Female, Humans, Language, Male, Pharmacists, Poland, Surveys and Questionnaires

Background

Global trends of patient migration, both within and outside medical tourism, mean that various medical professions, including pharmacists, are increasingly faced with dealing with non-Polish-speaking patients [1,2]. According to data from the Polish Central Statistical Office (GUS) from 2018, there were approximately 327 000 legally residing immigrants declaring permanent residence (0.86% of the population), which according to OECD data is the lowest number of registered immigrants among all European Union countries, but forecasts indicate that immigration processes in Poland will gain momentum [3].

The growing number of immigrants creates a need to facilitate access to health care services for these people, such as for pharmaceutical services in community pharmacies. This situation can create linguistic problems that would make it impossible to perform the service properly [4–6]. Proper pharmacotherapy, which is based on multi-level cooperation between the pharmacist, the patient, and the medical team, would not be fully possible if the staff of hospitals or pharmacies were unable to fully inform the patient about the rules for taking the medicines, the possible side effects, and the need to monitor any adverse effects [7]. The growing number of immigrant patients and the relatively low number of medical staff trained in specialist foreign medical language in Poland means that errors in communication between the doctor or pharmacist and the patient will become more commonplace. This situation can create obvious barriers to accessing care [8].

The pharmacist, as a person responsible for providing information on the correct use and dosage of medicinal products, interactions, and medical prophylaxis, becomes an important level of patient care. Even those immigrants who speak Polish in everyday situations while in Poland may not be able to adequately provide information or understand messages given to them when confronted with a situation in which professional medical vocabulary is used. This problem is also reflected in the understanding of information contained in medicinal leaflets, which determine the appropriate use of medicine. The information provided by manufacturers may not be linguistically suitable for immigrants [9]. Patients speaking non-Polish languages are therefore at a high risk of developing a medication error [1,10].

The problem of the relationship between the pharmacist and the non-Polish-speaking patient in Poland is relatively poorly understood, and requires better understanding and recognition of the barriers to communication and the provision of high-quality services. In Poland, there are no publications in this area or conclusions that could improve the quality of patient service. Defining the difficulties in communication may contribute to the development of an appropriate continuous training methodology for pharmacists, which may prove particularly valuable in light of upcoming changes in the development of pharmaceutical care.

Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the reported challenges for Polish community pharmacists in the provision of services to immigrants and non-Polish-speakers in 2018.

Material and Methods

The study was approved by Ethics Committee at the Collegium Medicum in Bydgoszcz, Poland (KB 264). We confirm that consent was received from the study participants and that the guidelines outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki were followed.

The survey took the form of an anonymous online questionnaire and comprised a group of 98 pharmacists who were willing to participate in the study. A total of 800 M.Pharm and pharmacy technicians from 30 of Poland’s largest cities were invited to take part in the study. The questionnaires were sent to pharmacists’ email addresses in cooperation with pharmacy councils. The survey was conducted in 2018.

The self-design survey consisted of 10 questions and a metric (gender, age, place of residence, number of patients served during the day). The questions aimed to determine the population of non-Polish-speaking patients served in pharmacies, to assess the preparedness of Polish pharmacies to provide services, and to assess the level of English proficiency among the staff. In addition, coping skills in handling non-Polish-speaking patients were also analyzed. The last 3 aspects were examined using a 5-point Likert scale assigned to the statements that the respondents rated.

Results

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE STUDY GROUP:

The study group was 84.7% women and 15.3% men. According to the breakdown by profession, 93 pharmacists and 5 pharmacy technicians participated in the survey. The age structure ranked the respondents according to 5 age groups: up to 28 years (38.8%), 28–35 years (27.6%), 35–42 years (26.5%), 42–49 years (4.1%), and over 49 years of age (3.1%).

Respondents mostly lived in cities with populations over 500 000 (43.9%, mainly residents of Warsaw), followed by cities with populations up to 200 000 (21.4%), cities with a population between 200 000 and 350 000 inhabitants (19.4%), and cities with a population between 350 000 and 500 000 inhabitants (15.3%).

Of those surveyed, 6% of respondents worked in a pharmacy serving no more than 50 patients per day, 38% of respondents served 50–100 patients per day, 32% served 100–150 patients per day, and 24% served more than 150 patients per day.

ANALYSIS OF THE NON-POLISH-SPEAKING PATIENT POPULATION:

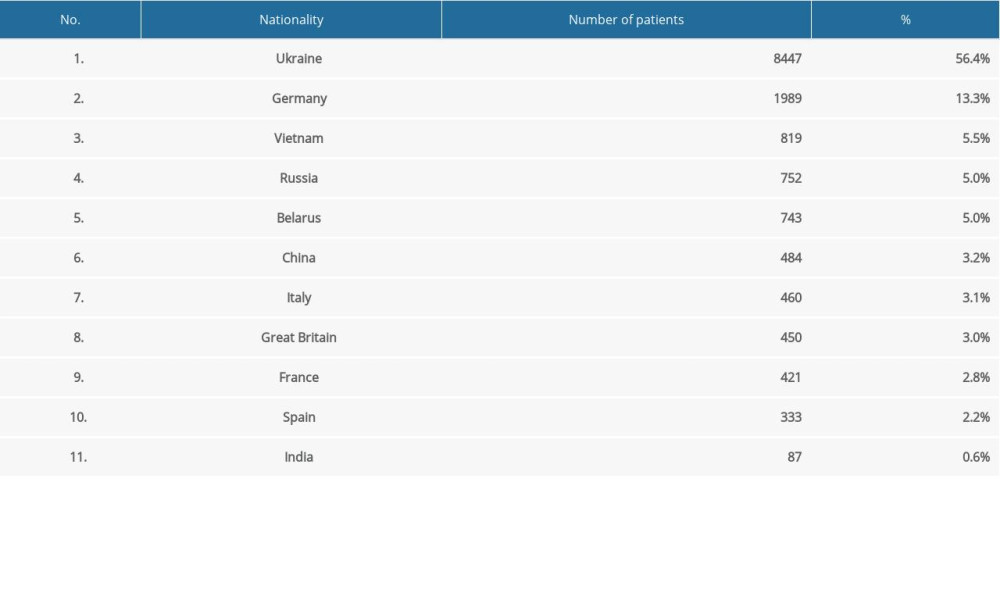

In the questionnaire, respondents indicated the nationalities of patients they served. The person to whom the medicinal product was dispensed was informed of the voluntary nature of the response and that it would not be processed for other than scientific purposes. We excluded 113 patients who did not agree to provide their nationality. Table 1 illustrates the percentages of nationalities served.

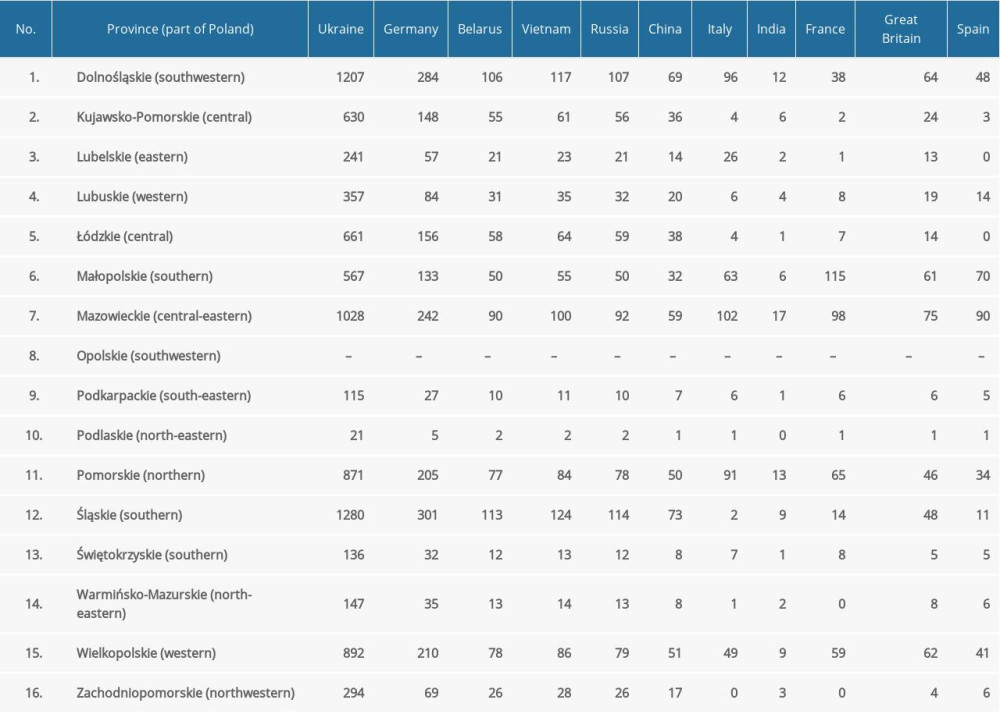

To illustrate the exact distribution of the population of patients served, the nationalities of the non-Polish-speakers were also divided according to the provinces in which the pharmacy was located (Table 2).

ASSESSMENT OF THE PREPAREDNESS OF PHARMACY STAFF TO PROVIDE SERVICES TO NON-POLISH-SPEAKERS:

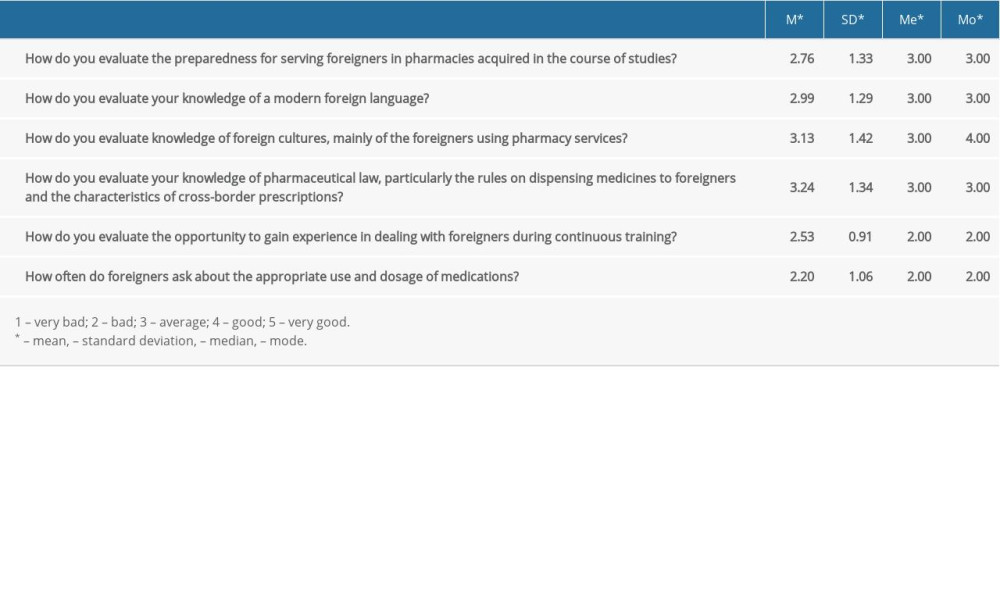

Only 28% of the respondents rated as good or very good their preparation to serve non-Polish-speakers on an equal footing with Polish patients. Most respondents rated their preparation as average (27%), or as ‘bad’ (22%) or ‘very bad’ (23%).

Respondents largely rated as ‘average’ (40%) their knowledge of pharmaceutical law, particularly the rules on dispensing medicines to non-Polish-speakers and the characteristics of cross-border prescriptions. Only 9% rated their knowledge of the law as very bad and 14% as bad. A total of 37% of pharmacists rated their level of knowledge of regulations on patient care in the Polish health service, including non-Polish-speakers, as higher than average.

In the next part of the survey, respondents were asked about their knowledge of a modern foreign language. The distribution of language proficiency scores was close to a normal distribution, with 26% of respondents rating their language proficiency as average, 39% rating their language proficiency negatively, and 36% of respondents rating their level of proficiency as good or very good. The respondents were then asked to rate their knowledge of foreign cultures. The respondents’ evaluations are almost evenly distributed: 35% of the respondents have a negative opinion of their own knowledge of foreign cultures, while 46% have a positive opinion.

Among the respondents, different answers were observed in each question regarding the preparation acquired in the course of studies or basic skills in working with other people, with a high standard deviation for all questions (standard deviation 1.20–1.42). The respondents rated the preparation acquired in the course of studies for providing comprehensive services to non-Polish-speakers as mean 2.76 and knowledge of a modern foreign language as mean 2.99. Knowledge of foreign cultures was rated above average (mean 3.13) and knowledge of legal regulations, mainly issues regulating cross-border prescriptions, had the highest score (mean 3.24) (Table 3).

No statistically significant relationship was found between young age and positive assessment of knowledge of a modern foreign language (

The opportunity to gain experience in dealing with non-Polish-speakers, during continuous training, was rated lowest by the respondents. More than half of the respondents (52%) negatively rated the opportunity to improve their knowledge of non-Polish-speaking patients during training. The educational syllabus was assessed as average by 35% of the respondents, and positively by only 13% of the respondents. Overall, the offer of specialized continuous training in terms of serving non-Polish-speakers was rated as below average (mean 2.53; ±0.91). The scores were very close to one another, as evidenced by the low standard deviation (0.91).

To obtain information about the quality of communication between pharmacy staff and non-Polish-speaking patients, the respondents were asked about the frequency of questions about appropriate pharmacotherapy and the problems faced by pharmacy staff. In the course of the study, it turned out that non-Polish-speaking patients only occasionally asked for information on correct pharmacotherapy (65%), a quarter asked to an average degree (comparable to Polish-speaking patients), and in only 10% of non-Polish-speaking patients frequently or very frequently asked for information on the use of medicinal products. The results show that non-Polish-speaking patients rarely asked about appropriate pharmacotherapy (mean 2.20). A significant association was observed between the size of the city in which the study was conducted and the frequency of questions from non-Polish-speakers about the principles of appropriate pharmacotherapy (

The problems most frequently encountered by respondents related to a lack of knowledge of professional medical language or a fear of the message being incorrectly understood by the patient (68%). One in 4 respondents indicated a lack of confidence in their knowledge of the procedures for filling prescriptions for non-Polish-speakers, including cross-border prescriptions. Only 7% of the respondents admitted that the lack of knowledge of the culture of non-Polish-speaking patients and the fear of tactless behavior were major problems in their daily practice.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this survey is the first to assess the ability to serve non-Polish-speakers in Polish pharmacies. Our research indicates that the most frequently served foreign nationalities in Poland were Ukrainians, Germans, Belarusians, and Vietnamese. Regardless of the province, these 4 nationalities accounted for the majority of non-Polish-speaking patients served. Citizens of Western countries, such as France, Spain, or the United Kingdom, preferred mainly tourist cities, such as Warszawa [Warsaw], Wrocław, Kraków [Cracow], or Trójmiasto (Gdańsk, Sopot, Gdynia), which may indicate the short-term non-profit character of their stay in Poland (eg, tourism).

An additional factor influencing the different national structure of the population of patients served is the phenomenon of dispensing medicinal products to non-Polish-speakers in border pharmacies. The possibility for patients to obtain medicinal products across borders is guaranteed by the so-called cross-border prescription. It is a prescription within the meaning of, inter alia, 3(K) of Directive 2011/24/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 9 March 2011 on the application of patients’ rights in cross-border healthcare (OJ of the EU L 88, 04 April 2011, p. 45), issued by the prescriber, at the request of a patient who intends to fill it in a European Union Member State other than the Republic of Poland.

The prices of most medicines in Polish pharmacies are significantly lower compared to those in Western European countries, which also significantly affects the frequency with which Polish pharmacies serve non-Polish-speaking patients. This is a result of government policy, which consists, among other things, of reimbursing a wide list of medicines so as to ensure their universal access. Regulation of the prices of medicinal products did not result from the laws of supply and demand determined by the market, but rather by arrangements in negotiations with pharmaceutical companies. This has given impetus for increased trade in medicines at the western Polish border, not only by exporters of medicinal products, but also by pharmacy workers legally fulfilling their employment obligations.

The surveyed pharmacists, when serving non-Polish-speaking patients, rated the knowledge gained during their studies as below average. It should be added, however, that the scores were almost evenly distributed, and the standard deviation of the results from the mean may indicate an imbalance between the levels of medical universities in Poland and the different emphasis on issues of professional communication and pharmaceutical care for non-Polish-speaking patients.

Pharmacy staff rate their knowledge of pharmaceutical law as average, including regulations on cross-border prescriptions or the conditions for allocating medical care to immigrants with different legal statuses. The answers given on this issue gave the impression of a lack of interest in the subject and of referring strictly to knowledge of the legal regulations for Polish patients (eg, modes of prescription, payment, or additional competence).

There was also a correlation between the positive evaluation of the preparedness for serving non-Polish speakers acquired in the course of studies, knowledge of a modern foreign language, and the size of the city the respondent came from. The multicultural character of Poland’s largest cities has a positive impact on the language skills of the respondents and allows them to develop their skills in this respect. A low demographic diversity, characteristic of smaller cities, may lead in the long term to the disappearance of language skills due to non-use. These conditions may lead to the creation of certain cognitive ‘shortcuts’ and a routine approach to fulfilling their duties, treating all patients as if they were Polish-speakers.

The respondents rated the opportunity to broaden their competences during continuous training, a key element of pharmacist education, as lowest. In light of the changing demography of patients, it may be considered necessary to adapt the educational syllabus for pharmacy staff, aiming at equalizing the possibilities for professional and appropriate coordination of pharmacotherapy for patients, regardless of their nationality, culture, or language.

The results of our study are difficult to compare with others, as studies on patient satisfaction with services in pharmacies are mainly found in the literature [11–13], and they rarely surveyed non-Polish-speaking patients. However, similar results are observed in the few available international publications. For example, Cohen et al point out that in Swiss pharmacies, half of the pharmacists are confronted weekly with serving patients in a foreign language to whom they cannot fully provide applicable information due to a lack of language skills. In many cases, translations are done by minors, and pharmacies employ multilingual staff wherever possible to prevent such situations [14]. In pharmacies in the United States, 64% of pharmacists indicate that they have situations where they are unable to explain medication regimens to patients due to the patient’s incomplete English language skills [15].

Despite the culturally and linguistically friendly conditions provided in Polish pharmacies, non-Polish-speaking patients are reluctant to ask about the correct treatment process, the correct way to of take medication, or the proper dosages. This may be due not only to a lack of Polish language skills among non-Polish-speakers, but also to cultural circumstances. Lack of interaction with pharmacy staff may also result from a lack of trust in Polish pharmacists or the perception of doctors as the only reliable source of information on pharmacotherapy. Unfortunately, in the world of Polish health care, there is a lack of activity aimed at convincing non-Polish-speaking patients of the high competence of Polish medical personnel. Communication barriers also mean that the pharmacists themselves do not provide information about the medicines [2,3]. This situation may influence a perceived lower satisfaction with health care among non-Polish-speakers compared to fluent Polish-speakers [16]. Moreover, this situation may influence non-adherence or reduced adherence to treatment recommendations and, consequently, delay achievement of the expected clinical result [2].

Respondents indicated that the lack of knowledge of professional pharmaceutical communication in a foreign language is the main problem they encounter in serving non-Polish-speakers during their daily practice. This problem can be directly attributed to the insufficient number of hours of foreign language classes in the course of study. Similar results are described by Cleland et al, indicating that the most common problems in serving non-nationals (migrants) in pharmacies include: communication, confidentiality (as conversations are usually interpreted by third parties, eg, family members), and duration of consultations [1]. Research conducted in Denmark confirms these results, although it indicates that the skills of serving immigrants may depend on the level of education of the staff [17].

The European Union is taking a number of initiatives to improve the quality of service provision in multicultural and international health care in Europe and to equalize the level of medical care between member states. One example is the Health for Growth Programme 2014–2020 [18]. This is the third multi-annual programme by the EU on health and has 4 specific objectives: (1) health promotion, disease prevention, and the creation of environments conducive to a healthy lifestyle, taking into account the principle of ‘health in all policies,’ (2) protecting EU citizens from serious cross-border health threats, (3) increasing the innovation, efficiency, and sustainability of health systems, and (4) facilitating EU citizen access to better and safer healthcare.

To meet these demands, the Polish health service needs to adopt international standards, familiarizing itself with the cultural conditions of the inhabitants of Europe and, above all, promoting learning of foreign languages. In a report published in 2015 by the European Union, Poland is ranked 29th among 37 countries in the Innovation Index of Countries according to the European Commission’s 2015 methodology, placing it in the group of moderate innovators [19].

The role of communication between health professionals and patients was also emphasized by the World Health Organisation in its report on the safety of medicines, which indicates that effective communication is key to minimizing the risks associated with the inappropriate use of a medicine [20]. The increased risk of an adverse drug reaction associated with use of the drug by non-Polish-speakers who do not fully speak the language of the country in which they consult the pharmacist (visit to the pharmacy) is indicated by many authors [6,14]. In Poland, in light of the planned pharmaceutical care, the pharmacist has the opportunity to become a full member of the primary health care team. The planned changes should therefore not only concern the possibility of extending the competences of pharmacy staff or the plan for more efficient management of the national budget, but also point out how important it is to educate current and future pharmacy staff for life in a multinational society.

Several solutions can be applied to improve the quality of service to foreign patients. In addition to the professional development of pharmacists, including learning a foreign language and the ability to talk to a non-Polish-speaking patient, it is worth highlighting other possible solutions, such as use of pictograms or translation software/apps.

We are aware that our research has limitations. First of all, the study enrolled a small group of pharmacists. Additionally, due to the lack of a validated questionnaire, we used a questionnaire of our own design. Moreover, we are aware that serving non-Polish-speakers involves 2 groups of people: patients living in Poland visiting a community pharmacy without Polish proficiency, and non-Polish citizens presenting themselves in Polish community pharmacies. In these 2 groups, other problems may occur, but the lack of health literacy and the inability to understand explanations are more common in the first group of people.

Conclusions

This study showed that in 2018, pharmacy staff in Poland did not feel adequately prepared to provide comprehensive pharmacy services for immigrants and non-Polish-speakers and had concerns of non-compliance with medications due to poor communication.

Language barriers and cultural differences can significantly affect the effectiveness of communication between health professionals and patients. Our survey respondents did not feel well prepared to provide comprehensive pharmaceutical services to non-Polish-speakers. Respondents negatively assessed both the syllabus of continuous training in terms of providing knowledge on how to properly serve non-Polish-speakers and the level of preparation gained at university to provide services to this group of patients. Given the risk of exposing non-Polish-speaking patients to medication errors, there is a need to implement comprehensive pharmaceutical care reforms as soon as possible, with particular emphasis on creating awareness among Polish pharmacists about cultural and linguistic differences in serving non-Polish-speakers. It is necessary for pharmacists to ensure foreign language proficiency, which will significantly affect the effectiveness of communication with patients and improve the quality of care provided.

References

1. Cleland JA, Watson MC, Walker L, Community pharmacists’ perceptions of barriers to communication with migrants: Int J Pharm Pract, 2012; 20; 148-54

2. Håkonsen H, Lees K, Toverud EL, Cultural barriers encountered by Norwegian community pharmacists in providing service to non-Western immigrant patients: Int J Clin Pharm, 2014; 36; 1144-51

3. : Office for Foreigners [cited 2021 Jun 6]. Available from: URL: [in Polish]http://www.migracje.gov.pl/statystyki/zakres/polska/typ/dokumenty/widok/tabele/rok/2018/

4. O’Brien CE, Flowers SK, Stowe CD, Desirable skills in new pharmacists: J Pharm Pract, 2017; 30; 94-98

5. Luetsch K, Rowett D, Interprofessional communication training: benefits to practicing pharmacists: Int J Clin Pharm, 2015; 37; 857-64

6. Schwappach DL, Meyer Massetti C, Gehring K, Communication barriers in counselling foreign-language patients in public pharmacies: threats to patient safety?: Int J Clin Pharm, 2012; 34; 765-72

7. Meuter RF, Gallois C, Segalowitz NS, Overcoming language barriers in healthcare: A protocol for investigating safe and effective communication when patients or clinicians use a second language: BMC Health Serv Res, 2015; 15; 371

8. Norouzinia R, Aghabarari M, Shiri M, Communication barriers perceived by nurses and patients: Glob J Health Sci, 2015; 8; 65-74

9. Bowen S: Language barriers in access to health care, 2003, Canada, Health Canada

10. Wheeler AJ, Scahill S, Hopcroft D, Stapleton H, Reducing medication errors at transitions of care is everyone’s business: Aust Prescr, 2018; 41; 73-77

11. Iskandar K, Hallit S, Raad EB, Community pharmacy in Lebanon: A societal perspective: Pharm Pract (Granada), 2017; 15; 893

12. Awad AI, Al-Rasheedi A, Lemay J, Public perceptions, expectations, and views of community pharmacy practice in Kuwait: Med Princ Pract, 2017; 26; 438-46

13. Rodgers RM, Gammie SM, Loo RL, Comparison of pharmacist and public views and experiences of community pharmacy medicines-related services in England: Patient Prefer Adherence, 2016; 10; 1749-58

14. Cohen AL, Rivara F, Marcuse EK, Are language barriers associated with serious medical events in hospitalized pediatric patients?: Pediatrics, 2005; 116; 575-79

15. Bradshaw M, Tomany-Korman S, Flores G, Language barriers to prescriptions for patients with limited english proficiency: A survey of pharmacies: Pediatrics, 2007; 120; e225-35

16. Harmsen JA, Bernsen RM, Bruijnzeels MA, Meeuwesen L, Patients’ evaluation of quality of care in general practice: What are the cultural and linguistic barriers?: Patient Educ Couns, 2008; 72; 155-62

17. Mygind A, Espersen S, Nørgaard LS, Traulsen JM, Encounters with immigrant customers: Perspectives of Danish community pharmacy staff on challenges and solutions: Int J Pharm Pract, 2013; 21; 139-50

18. European Commission [cited 2021 May 12]. Available from: URL: http://www.ec.europa.eu/health/funding/programme_en

19. European Commission [cited 2021 May 11]. Available from: URL: http://www.ec.europa.eu/growth/industry/innovation/facts-

20. World Health Organization: Medication without harm – Global patient safety challenge on medication safety, 2017, Geneva, WHO

In Press

15 Apr 2024 : Laboratory Research

The Role of Copper-Induced M2 Macrophage Polarization in Protecting Cartilage Matrix in OsteoarthritisMed Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943738

07 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Knowledge of and Attitudes Toward Clinical Trials: A Questionnaire-Based Study of 179 Male Third- and Fourt...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943468

08 Mar 2024 : Animal Research

Modification of Experimental Model of Necrotizing Enterocolitis (NEC) in Rat Pups by Single Exposure to Hyp...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943443

18 Apr 2024 : Clinical Research

Comparative Analysis of Open and Closed Sphincterotomy for the Treatment of Chronic Anal Fissure: Safety an...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.944127

Most Viewed Current Articles

17 Jan 2024 : Review article

Vaccination Guidelines for Pregnant Women: Addressing COVID-19 and the Omicron VariantDOI :10.12659/MSM.942799

Med Sci Monit 2024; 30:e942799

14 Dec 2022 : Clinical Research

Prevalence and Variability of Allergen-Specific Immunoglobulin E in Patients with Elevated Tryptase LevelsDOI :10.12659/MSM.937990

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e937990

16 May 2023 : Clinical Research

Electrophysiological Testing for an Auditory Processing Disorder and Reading Performance in 54 School Stude...DOI :10.12659/MSM.940387

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e940387

01 Jan 2022 : Editorial

Editorial: Current Status of Oral Antiviral Drug Treatments for SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Non-Hospitalized Pa...DOI :10.12659/MSM.935952

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e935952